The Three Hegemonies: How Sanskrit, Persian, and English Shaped—But Didn't Erase—India's Linguistic Soul

Introduction: Hegemony as Seduction, Not Just Domination

India’s linguistic history is often told as a story of successive invasions and impositions—a series of foreign languages forced upon a passive populace. But this narrative misses a more complex and fascinating truth. As Professor Ganesh Devy argues in his seminal Nehru Memorial Lecture, India has experienced three major linguistic hegemonies: Sanskrit, Persian, and English. Yet, none of them erased India’s native linguistic diversity. Instead, each hegemony was met with profound resistance, adaptation, and creative synthesis, ultimately enriching, rather than extinguishing, India’s linguistic soul.

This post explores Devy’s framework of the "three hegemonies," examining how each language gained influence not merely through force, but through cultural allure, technological advantage, and the consent of the governed—and how India’s multitude of languages not only survived but thrived under their shadow.

1. Sanskrit: The Hegemony of the Magical Word

Arrival & Nature of Power:

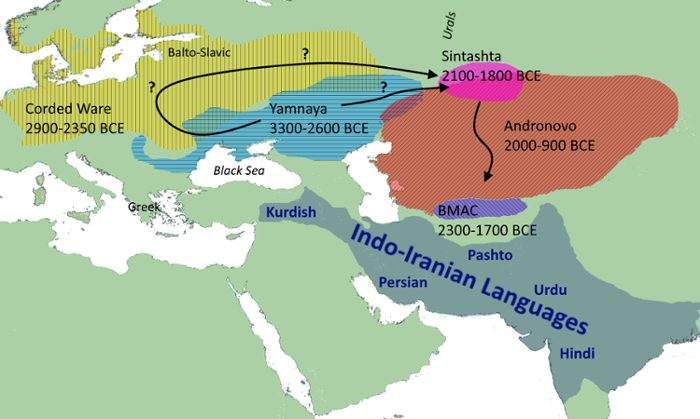

Sanskrit did not arrive in India with a massive population. It was brought by relatively small, nomadic groups. Its rise to hegemony was not based on military might but on something more potent: perceived sacredness and mystical authority.

Mechanisms of Hegemony:

- The Veil of Obscurity: As Devy explains, within centuries of the Vedas being composed, their original symbolic meanings were forgotten. What remained was a sonorous, ritualistic oral tradition—complex, enchanting, and accessible only to a priestly class (Brahmins). This created a "magical" aura around the language.

- Control of Knowledge: Access to this "magical word" became the basis for social hierarchy—the Varna system. Those who could recite and interpret the Vedas occupied the top of the social order, wielding linguistic authority to structure society.

- Technology of Memory: Sanskrit's hegemony was built on orality. Its intricate phonetic rules, metrical structures, and mnemonic systems allowed for vast textual preservation without writing, making it resilient and exclusive.

Resistance and Synthesis:

Sanskrit hegemony was never total. Resistance emerged in two key forms:

- The Suta Tradition: Epics like the Mahabharata (a suta literature, not mantra) democratized narrative. They were told by and for common people, weaving together multiple dialects and folk traditions, creating a counter-current of accessible storytelling.

- The Heterodox Revolt: Buddhism and Jainism explicitly rejected Vedic Sanskrit’s authority. They adopted Pali and Prakrit—languages of the people—for their teachings and scriptures. Emperor Ashoka used these vernaculars and regional scripts for his edicts, creating the first major political challenge to Sanskrit’s monopoly.

Despite this, Sanskrit showed remarkable absorptive capacity, assimilating words and ideas from Dravidian, Munda, and other language families, proving that hegemony could also be a two-way street of influence.

2. Persian: The Hegemony of Love and Paper

Arrival & Nature of Power:

Persian entered the Indian subcontinent through trade, Sufi mystics, and later, Delhi Sultanate courts. Its hegemony was distinct—it was not the language of a religious majority imposing theology, but the language of statecraft, elite culture, and mystical poetry.

Mechanisms of Hegemony:

- The Technology of Paper: Unlike Sanskrit’s orality, Persian’s power was amplified by paper. The availability of this relatively cheap medium from around the 13th century allowed for widespread administrative use, record-keeping, and literary circulation.

- The Culture of Love (Ishq): Persian brought with it the rich tradition of Sufi poetry and the ghazal, centering themes of divine and earthly love, tolerance, and spiritual yearning. This was a profoundly new aesthetic that captivated hearts across religious boundaries.

- Language of Opportunity: As Devy stresses, Persian was not a "Muslim" language in India. Hindus (like Shivaji’s secretaries) and Sikhs learned it for administration, poetry, and advancement. It became the lingua franca of the elite, a pragmatic choice for upward mobility.

Resistance and Synthesis:

The Bhakti movement (14th-17th centuries) was the great linguistic and cultural response to Persian hegemony.

- Vernacular Empowerment: Bhakti saints from Kabir (Hindi) to Tukaram (Marathi) to the Alvars (Tamil) rejected both Sanskrit formality and Persian courtly culture. They composed ecstatic poetry in the local languages of the people, democratizing divinity and challenging hierarchical authority.

- Birth of Modern Languages: This period saw the crystallization of modern Indian languages—Bangla, Marathi, Gujarati, Punjabi—as literary vehicles. Persian hegemony, rather than crushing them, provided a catalyst for their assertive self-expression. The languages absorbed Persian vocabulary related to governance, law, and culture, creating rich new lexicons (e.g., Hindi’s Farsi-ized Rekhta tradition).

Persian’s decline began with a political act: the 1835 English Education Act, which replaced it with English as the official language. Its legacy, however, is indelible in the vocabulary, administrative structures, and poetic soul of modern India.

3. English: The Hegemony of Modernity and Print

Arrival & Nature of Power:

English arrived with colonialism, but its hegemony was secured less by the sword and more by the promise of modernity, science, and access to a global world.

Mechanisms of Hegemony:

- The Technology of Print: The printing press, established by missionaries and colonial administrators, gave English an unprecedented advantage. It enabled standardization, mass production of textbooks (like Macaulay’s infamous "Minute"), and the creation of a new, English-educated bureaucratic class.

- The Window to the World: After a period of relative isolation, English opened up European Enlightenment thought, modern science, and political ideas (including liberty and nationalism) to Indian intellectuals.

- Language of the State: English became the unifying language of the pan-Indian anti-colonial movement (Nehru, Gandhi, Ambedkar all used it strategically) and, post-independence, the neutral link language of administration, higher judiciary, and pan-Indian discourse.

Resistance and Synthesis:

Ironically, English hegemony triggered the most powerful affirmation of India’s linguistic diversity.

- The Vernacular Renaissance: The 19th and early 20th centuries saw an explosion of literary activity in Indian languages. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (Bangla), Premchand (Hindi), Subramania Bharati (Tamil) produced masterpieces that were modern, political, and deeply rooted in their linguistic soil, often using the novel—a European form—to tell Indian stories.

- The Linguistic Reorganization of States (1950s-60s): This was the ultimate democratic resistance. India rejected the European model of "one language, one nation" and constitutionally reorganized its internal borders based on major languages. This was, as Devy calls it, a civilizational statement—a federal republic built on linguistic pride.

- The Nehruvian Compromise: Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s approach was pivotal. While promoting Hindi, he protected linguistic states and, crucially, allowed the 1961 census to record 1,652 mother tongues. This official recognition was a bulwark against homogenization.

Conclusion: The Uniqueness of India’s Linguistic Civilization

Devy’s analysis reveals a stunning paradox: each wave of linguistic hegemony, instead of creating monolingual submission, strengthened India’s multilingual resolve. Sanskrit provoked the vernaculars of Bhakti. Persian spurred the crystallization of regional literatures. English triggered the political consolidation of linguistic states.

The reason lies in what Devy identifies as India’s core civilizational fabric: it is not a monolith, but a "union of states"—a linguistic civilization. Its strength is diversity-in-conversation. Each hegemony provided a new vocabulary, a new technology, and a new stimulus, which Indian languages absorbed, adapted, and used to reinvent themselves.

Today, the threat is different. It is not a new linguistic hegemony, but the digital silence—the atrophy of human conversation, the loss of vocabulary, and the potential erosion of linguistic diversity itself. Yet, the historical lesson of the three hegemonies offers hope. It shows that India’s languages possess a remarkable resilience, born of a 5,000-year history of negotiating power, absorbing influence, and forever asserting the people’s voice. The soul of India does not reside in any one hegemonic language, but in the unending, vibrant, and defiant conversation between them all.

Further Reading / References:

- Ganesh Devy’s 2025 Nehru Memorial Lecture: "Language, Civilization and Hegemony."

- His analysis of Sanskrit’s "magical" authority vs. Persian’s "love" in various interviews.

- Historical works on the Bhakti movement and the Linguistic Reorganization of States.

- After Amnesia (1992) by Ganesh Devy, exploring the colonial encounter with language.

Comments (Write a comment)

Showing comments related to this blog.