What Aurangzeb Really was? What the Archives Actually Say

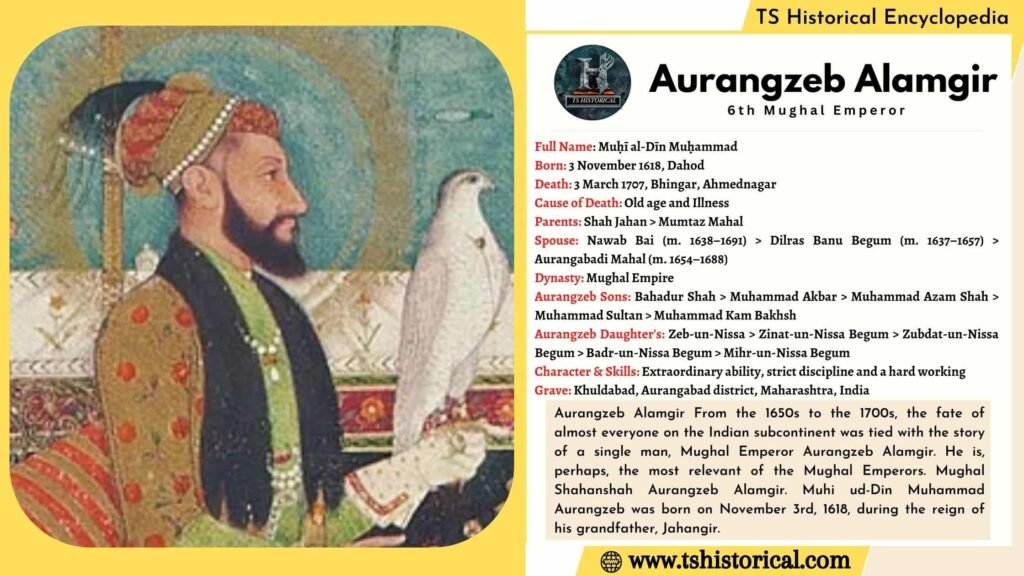

The name Aurangzeb Alamgir, the sixth Mughal Emperor who ruled from 1658 to 1707, evokes one of the most polarized debates in Indian history. In popular culture, political rhetoric, and even school textbooks, he is often cast as a religious fanatic, a temple-destroying bigot, and the archetype of oppressive Muslim rule. This image serves as a potent symbol in modern identity politics, but how does it stand up against the actual historical record? By moving beyond polemics and into the archives, a far more complex—and often surprising—portrait of the emperor emerges, one that challenges the simplistic caricature.

The Origins of the Myth: Why is Aurangzeb Singled Out?

To understand the controversy, we must first trace the myth's origins. As historian Audrey Truschke explains, the vilification of Aurangzeb is not a medieval invention but a modern political tool with two primary lineages:

- The British Colonial Narrative: Faced with the moral and logistical challenge of justifying their oppressive colonial rule, the British employed a classic strategy: "We may be bad, but the previous rulers were worse." They selectively translated Mughal chronicles, exaggerated accounts of tyranny, and promoted the idea that Mughal rule—with Aurangzeb as its pinnacle of intolerance—was a period of unrelenting religious persecution. This created a "civilizing" pretext for British intervention.

- Modern Hindu Nationalist Adoption: In the 20th century, Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) ideology adopted and amplified this British-era caricature. For a movement built on the idea of a pristine Hindu nation subjugated by foreign Islamic invaders, Aurangzeb became the perfect historical villain. This narrative serves a present-day political purpose, using the past to stoke communal sentiment and marginalize modern Indian Muslims by linking them to a tyrannical past.

As Truschke notes, "Hindu nationalists are the major intellectual inheritors of British-era ideas... and that includes how much they hate the Mughals." The myth is powerful not because it's accurate, but because it is useful.

What the Archives Reveal: A Nuanced Picture of Temple Policy

So, what does contemporary evidence from Aurangzeb's reign actually tell us about temple destruction? The record is nuanced and points to a policy driven more by political strategy than blind iconoclasm.

1. Temple Destruction as Political Warfare, Not Theology

The most critical insight from recent scholarship is that attacking temples was not a Muslim innovation in India. As Truschke and other historians like Richard Eaton have shown, the practice was a well-established form of political warfare in pre-modern India.

"The idea of targeting temples as a legitimate political practice... was developed and owned by Hindu kings long before we had Indo-Muslim rule," states Truschke. Dynasties like the Cholas and Pratiharas routinely desecrated rival kingdoms' temples because these structures were not just places of worship; they were symbols of royal authority, legitimacy, and treasury. Destroying a rival's temple was a direct attack on their sovereign power.

Aurangzeb operated within this existing Indian political framework. His orders for temple destruction almost always correlate with rebellions or political threats. For example:

- After the Jat uprising near Mathura, the Kesava Deva temple was demolished.

- Following the Maratha king Shivaji's son Sambhaji's continued rebellion in the Deccan, some temples in Maharashtra were targeted.

- Temples in Benares were destroyed in the aftermath of a suspected rebellion there.

In each case, the action followed a pattern of punishing rebellion and dismantling the political symbols of challengers. Temples in areas that remained loyal, however, were often left untouched and even granted land and protection.

2. The Overlooked Evidence of Temple Patronage

Contradicting the fanatic image, Aurangzeb's reign also issued numerous orders to protect Hindu temples, priests, and worship. Imperial farmans (orders) granted land for temples and maths (monasteries). The Somnath temple, famously, received grants during his rule. His administration routinely settled disputes between Hindu priestly orders and protected pilgrimage routes.

Why would a "fanatic" do this? Because Aurangzeb was, first and foremost, an emperor. His primary goals were stability, revenue, and control. Alienating the vast majority of his Hindu subjects through wanton destruction was counterproductive to statecraft. Much of his patronage was directed at Brahmins and institutions that helped legitimize Mughal rule and maintain the social order.

3. The Problem of Exaggerated Evidence

Modern claims often cite Mughal-era chronicles that boast of "destroying thousands of temples." Historians urge caution here. As Truschke points out, "The Mughals exaggerated the number of temples that they destroyed because to them it was a virtuous thing." Court chroniclers aimed to please the emperor by portraying him as a defender of Islam. Taking these poetic or boastful inscriptions at face value, without cross-referencing with other evidence like tax records, architectural remains, or non-courtly sources, is ahistorical.

The Man Versus the Myth: Aurangzeb's Contradictions

The archival Aurangzeb is a man of contradictions, which makes him a historical figure, not a cartoon villain.

- Reinstitution of the Jizya: This is a valid point of criticism. In 1679, Aurangzeb reinstated the jizya, a tax on non-Muslims. This was widely unpopular and criticized even by his own family. However, historians debate its primary motive. Truschke suggests it may have been less about revenue and more about placating the orthodox clerical class (ulama) by giving them tax-collecting jobs, thereby consolidating his political control.

- Employment of Hindus: Throughout his reign, Hindus constituted a significant portion of his administration, army, and nobility. The highest-ranking general in his army for much of his reign was Rajput Raja Jai Singh, who led campaigns against other Hindu rulers like Shivaji. His administration was a multi-religious enterprise.

- Personal Piety vs. Political Pragmatism: While personally devout, Aurangzeb's actions were often pragmatic. He spent decades in the Deccan wars not to convert the populace, but to crush the Maratha Empire and the Shia kingdoms of Bijapur and Golconda—a fight for territory and sovereignty.

Conclusion: Why a Fact-Based History Matters

Dismantling the myth of "Aurangzeb the fanatic" is not about whitewashing a Mughal emperor or downlining the undoubted brutality of pre-modern warfare and rule. It is about pursuing historical accuracy over political convenience.

The simplified, hateful caricature of Aurangzeb has real and dangerous consequences in the present. It acts as a dog whistle, legitimizing the harassment of modern historians and, more perniciously, fueling violence and discrimination against contemporary Indian Muslims, who are wrongfully held accountable for the actions of a ruler from 300 years ago.

Engaging with the complex, archive-based history of figures like Aurangzeb does a vital service. It reminds us that the past was not a simple battleground of monolithic religions, but a tapestry of political calculation, strategic alliances, and contradictions. In an age where history is so often weaponized, such nuanced understanding is not just academic—it is essential for fostering a more informed and less divisive present.

Comments (Write a comment)

Showing comments related to this blog.