Writing Transitions: The Three C

Introduction: The Foundation of Great Transitions

You've learned why transitions matter and explored five powerful techniques. But regardless of which technique you use, all effective transitions share three fundamental qualities.

If you've attended workshops on screenwriting style, you might be familiar with the Three C's of writing:

- Clarity

- Concision

- Color

These same principles apply to transitions—with one important adjustment. For transitions, the third C becomes Compelling rather than "Color." Let's explore why these three qualities are non-negotiable for effective scene transitions.

The First C: Clarity

Definition: When you're in your normal flow and don't want to stop the audience at a juncture of an act or sequence, the transition must be clear. We need to understand where we are, and there needs to be an element of continuity.

Why Clarity Matters

The worst thing that can happen during a transition is that your audience loses track of the story. If viewers have to stop and figure out:

- Where are we?

- When are we?

- Who is this?

- What's happening?

...then you've broken their engagement with your story. They're no longer experiencing your narrative—they're trying to solve a puzzle.

Creating Clear Transitions

Use continuity elements:

When we land in a new scene, we should feel at home. We shouldn't be disoriented or have to figure things out before we can return to the story.

Think of continuity elements as handrails for your audience:

- A character we recognize

- A prop or object we've seen before

- A visual motif that's been established

- A thematic thread we're following

- A question we're waiting to be answered

Example 1: Monsters, Inc. (Illustration Technique)

End of Previous Scene:

The company president gives a speech about the kind of scarers they need. He builds to a declaration: "I need scarers like... like... James P. Sullivan!"

[TRANSITION]

Start of Next Scene:

We cut directly to James P. Sullivan (Sulley) waking up in his apartment, starting his day.

Why it's clear: The verbal announcement of the character's name immediately before we meet him creates perfect clarity. We know exactly who we're looking at and why he matters. There's no confusion, no disorientation—just seamless forward momentum.

This is a variation on the Question/Answer technique, but focused on clarity through illustration. The previous scene announces what we're about to see, and the next scene illustrates it.

Example 2: The Matrix (Anticipation Through Illustration)

End of Previous Scene:

A lieutenant on the phone says confidently: "I think we can handle one little girl."

[TRANSITION]

Start of Next Scene:

We see the aftermath—officers down, chaos, destruction.

Then we hear: "No, Lieutenant. Your men are already dead."

Why it's clear: We anticipated seeing the confrontation with "one little girl." When we see the aftermath instead, we immediately understand what happened—and that the lieutenant drastically underestimated the threat. The illustration gives us a different slant than expected, but it's perfectly clear.

When Illustration Is Essential

Sometimes illustration isn't just about smooth transitions—it's about guiding the audience through potentially confusing story moments:

Example: Little Women (1994)

The Challenge: Moving from one season to another, which could be disorienting.

The Solution: Voiceover narration by one of the characters:

"In the spring, we turned Orchard House upside down with preparations for Meg to attend Sally Moffat's coming out."

Why it works: The narration acts as a lubricant, helping the audience glide smoothly into a new time period without confusion. It clarifies when we are and what's happening, preventing the audience from losing the plot.

Julian Armstrong's Little Women screenplay uses this technique specifically for time transitions, making what could be jarring shifts feel natural and clear.

The Golden Rule of Clarity

If you're not 100% sure the viewer will understand where/when they are in your new scene, add a clarifying element. This might be:

- A line of dialogue that orients us

- A visual callback to something familiar

- A title card (use sparingly!)

- Voiceover narration

- An establishing shot that clearly shows time/place

Clarity should never be sacrificed for style. A confused audience is a disengaged audience.

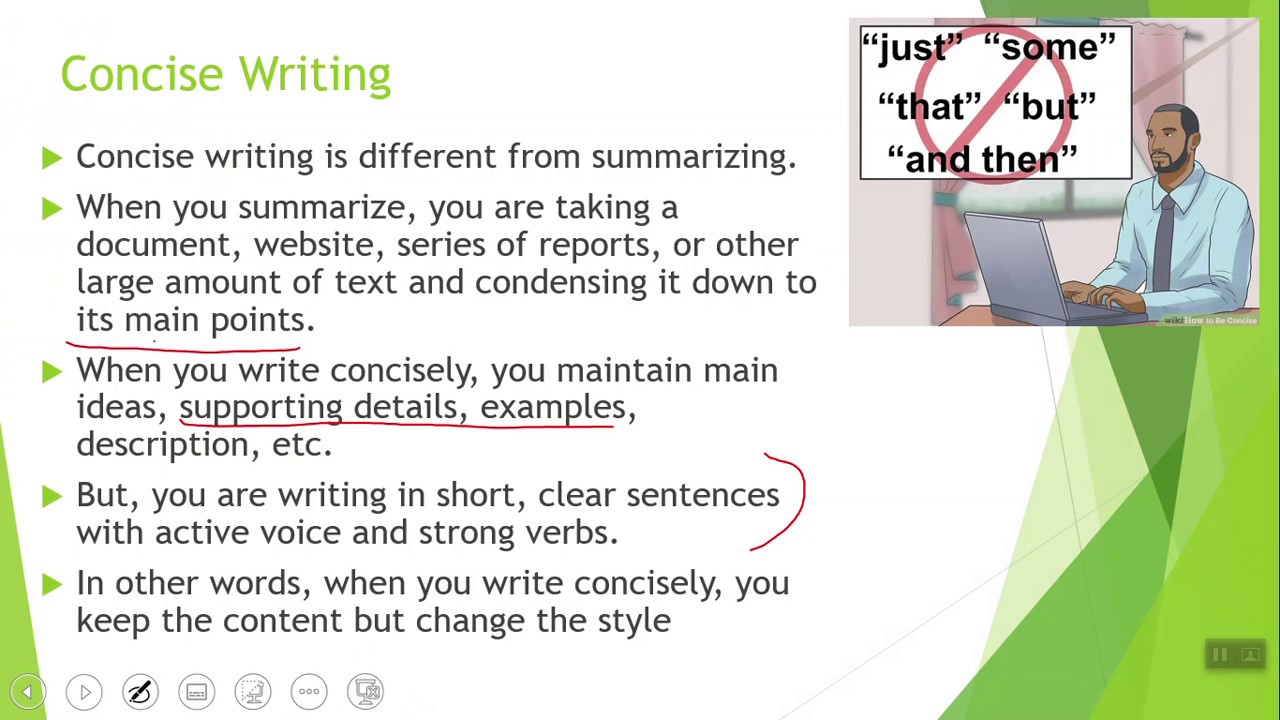

The Second C: Concision

Definition: Your transition needs to be brief. Don't waste the audience's time. Keep the story moving.

The Hitchcock Principle

Alfred Hitchcock famously said: "Drama is life with the dull bits cut out."

That's exactly what concision in transitions means—cutting out the boring bits.

Example 1: Rain Man (The Ellipsis)

What we see:

- Raymond and Charlie get in the car

- They start driving

- [TRANSITION - we see brief shots of the car on the highway]

- They arrive at their destination

What we don't see:

- The entire hours-long drive

- Rest stops

- Gas stations

- Traffic

- All the mundane details of travel

Why it works: We can tell from context that a lot of driving happened, but it wasn't interesting to the story. We cut straight from departure to arrival, maintaining momentum.

This is called an ellipsis—leaving out the uninteresting bits. It's one of the most common forms of transition you'll use, and you probably do it without even realizing it.

Example 2: Little Miss Sunshine (Double Transition)

This midpoint reversal shows perfect concision through two quick transitions:

Scene 1: Grandfather dies in the hospital

FADE TO BLACK (major story break)

Scene 2: The family in a diner, Olive asking: "Where's Grandpa?"

CUT TO: (immediate response to her question)

Scene 3: Grandpa's body wrapped in a sheet in the van

What got cut:

- Dealing with hospital paperwork

- Discussions about what to do

- The actual act of taking the body

- Driving to the diner

- Ordering food

What we get: Only the essential story moments. The fade to black signals major change, then we immediately jump to the consequence of their decision. No time is wasted.

The Barry Lyndon Counter-Example

There's a transition in Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon that violates the concision principle—and it's a perfect example of what NOT to do in modern screenwriting:

The Scene: A character makes an appointment for the hero. We cut to the hero at that appointment. So far, so good—that's efficient.

The Problem: The shot goes from close-up to extreme wide, and it takes about 30 seconds.

Thirty seconds might not sound like much, but in transition terms, it's an eternity. The story isn't moving forward; we're just watching the camera pull back.

Would This Work Today?

Probably not—unless you're writing for:

- An art house audience

- A film festival

- A director with complete artistic freedom

If you're writing professionally, for commercial cinema or television, your transitions must be concise. Modern audiences have shorter attention spans and expect continuous forward momentum.

How to Achieve Concision

Ask yourself these questions:

- What's the last essential moment of this scene? Cut everything after that.

- What's the first essential moment of the next scene? Start there, not before.

- Can I eliminate "in-between" action? (Getting in cars, walking through doors, greetings, goodbyes—unless they're dramatically important)

- Am I repeating information the audience already knows? Cut it.

- Does this transition actively move the story forward? If not, reconsider it.

The Motion Technique

One powerful way to maintain concision while creating smooth transitions is through motion and movement.

In the Rain Man example, we saw the car in motion. This technique works because:

- It signals time passing without dwelling on it

- Movement implies progress

- It creates visual interest

- It maintains energy and momentum

Other examples of motion in transitions:

- A plane taking off, then landing

- A character running, then arriving

- Wheels turning, then stopping

- A door closing, then opening in a new location

Motion creates a sense of forward momentum that keeps your story moving briskly.

The Third C: Compelling

Definition: Your transition needs to either propel us forward invisibly OR be fun and memorable enough to elevate the cinematic experience.

This breaks into two categories:

Category 1: Compelling as Anticipation (Invisible Transitions)

When your transition needs to be smooth, elegant, seamless, and unconscious, you create compulsion through anticipation.

The Question/Answer technique is the perfect example:

Remember Titanic: "So, you want to go to a real party?"

This question compels us into the next scene. We WANT to know what happens next. We won't even notice the transition because we're pulled forward by curiosity and anticipation.

Other ways to create anticipation:

- End on a moment of tension or danger

- Create a mystery that demands resolution

- Show a character making a decision, then show the consequence

- Hint at something important about to happen

The audience is so engaged with "what happens next?" that the scene transition becomes invisible.

Category 2: Compelling as Memorable (Noticeable Transitions)

When you want to highlight the transition—usually at major structural points in your story—"compelling" means creating something fun, surprising, or cinematically elevated.

Example 1: Highlander (The Car Park Misdirection)

We discussed this in the previous post, but it bears repeating: This transition is compelling because it's surprising and delightful.

When the camera movement reveals we've jumped from a modern car park to the medieval Scottish Highlands, it's unexpected, clever, and memorable. It elevates the cinematic experience.

"I saw this movie in the 1980s," the instructor notes, "and I still remember that transition."

That's the power of a compelling, noticeable transition.

Example 2: 2001: A Space Odyssey (The Bone-to-Spacecraft Cut)

The most famous match cut in cinema history: a bone thrown into the air by an ape-man transitions into a spacecraft millions of years in the future.

This is compelling because it's:

- Visually striking (the shapes match)

- Intellectually stimulating (the thematic connection between tools/weapons)

- Cinematically bold (jumping millions of years in a single cut)

- Emotionally resonant (commenting on human evolution)

It's a transition you don't just watch—you remember it, think about it, and discuss it.

When to Use Each Type

Use invisible, anticipation-based transitions:

- For most of your screenplay (80-90% of transitions)

- During continuous action sequences

- When maintaining tension

- In the middle of acts

- When you want seamless flow

Use noticeable, memorable transitions:

- At act breaks

- At major turning points in the story

- When shifting tone dramatically

- To emphasize thematic points

- When transitioning between different timelines or worlds

- When you want to give the audience a "breather"

The Risk of Over-Styling

Here's an important warning: Don't make every transition "compelling" in the memorable sense.

If every transition is a showstopper, then:

- Nothing stands out

- The audience becomes exhausted

- The story gets lost in the technique

- Readers/viewers feel manipulated

Save your most compelling, noticeable transitions for moments that truly matter structurally or thematically.

Balancing the Three C's

The three C's work together and sometimes create tension:

Clarity vs. Concision:

Sometimes you need a bit more time/space to create clarity. That's okay. Clarity always wins over concision—a confused audience is worse than a slightly slower pace.

Concision vs. Compelling:

A truly compelling transition might take a moment longer. That's fine—but make sure it's worth it. The transition should be compelling enough to justify the extra beats.

Clarity vs. Compelling:

Misdirection transitions deliberately play with clarity, creating temporary confusion for dramatic effect. This works only if the confusion resolves quickly and satisfyingly.

The Priority Order

When in doubt, prioritize in this order:

- Clarity (without this, you've lost your audience)

- Concision (respect your audience's time)

- Compelling (elevate the experience when appropriate)

Practical Application: Analyzing Your Own Transitions

Take three transitions from your current screenplay and test them against the Three C's:

Transition 1: _________________

Clarity Check:

- Will the audience know where/when they are? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Is there an element of continuity? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Will they understand immediately what's happening? ☐ Yes ☐ No

Concision Check:

- Does it cut straight from the last essential moment to the first essential moment? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Have I eliminated "in-between" action? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Does it maintain forward momentum? ☐ Yes ☐ No

Compelling Check:

- If invisible: Does it create anticipation? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- If noticeable: Is it memorable and worth highlighting? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Does it serve the story? ☐ Yes ☐ No

Repeat for your other transitions.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake 1: Sacrificing Clarity for Style

Don't get so caught up in creating a "cool" transition that you confuse your audience.

Mistake 2: Lingering Too Long

Trust your audience. Get in late, get out early. Cut the boring bits.

Mistake 3: Making Every Transition a Showstopper

Save the dramatic, noticeable transitions for structural turning points. Most transitions should be invisible.

Mistake 4: Forgetting the Reader

Remember: most scripts are rejected at the reading stage. Your transitions need to work on the page, not just on screen.

Mistake 5: Over-Explaining

Don't write: "We cut to the next scene where John is in his office, having driven there from his house, parked his car, taken the elevator up, and walked down the hall."

Just write: "INT. JOHN'S OFFICE - DAY"

The Three C's Checklist

Before you finalize any transition, ask:

✓ Is it CLEAR? Will my audience know where they are?

✓ Is it CONCISE? Have I cut out the boring bits?

✓ Is it COMPELLING? Does it either pull them forward invisibly or provide a memorable moment?

If you can answer yes to all three, you've written an effective transition.

Coming up next: Time, Place, and Action: The Building Blocks of Scene Transitions - where we'll explore how these three fundamental elements define scenes and create opportunities for powerful transitions.

Comments (Write a comment)

Showing comments related to this blog.