How the Arabs Didn't Conquer—They Learned

The popular image of a conquering army is one of destruction: razing cities, scattering populations, and erasing the culture of the vanquished. The explosive expansion of the Arab Empires in the 7th and 8th centuries certainly involved conquest, but it followed a radically different script. The most remarkable story isn't how much they conquered, but what they chose to preserve and amplify.

The common narrative suggests that the Islamic Golden Age was a spontaneous eruption of knowledge. In reality, it was a deliberate, state-sponsored project of intellectual adoption. The Arabs didn't arrive with all the answers; they arrived with the humility to ask the right questions.

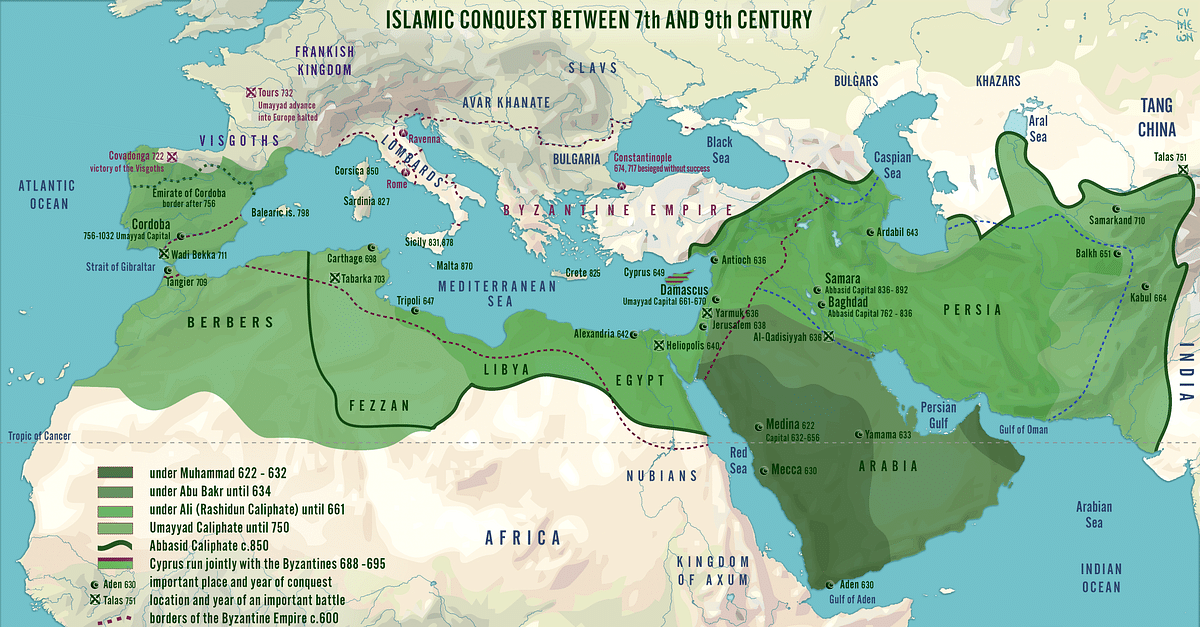

The Conquest of Knowledge, Not Its DestructionIn the 7th century, the newly unified Islamic state found itself the master of vast territories, having dismantled the Persian Empire and seized key provinces from the Byzantine (Roman) Empire. They were a minority ruling over ancient, sophisticated civilizations. The critical moment came not when the battles ended, but when the administration began.

Faced with the monumental task of governing, the Arab rulers did something extraordinary. They turned to the conquered Persians and said, in effect: "We don't know how to run an empire. You've been doing this for over a thousand years. Teach us."

This humility was the catalyst. The Arabs lacked complex bureaucracies, central mints, and agricultural science. Instead of imposing their own nascent systems, they absorbed and adapted the best practices of the Persians, Romans, and Indians. The first Arab coins, for instance, were crude counterfeits of Roman and Persian currency, a tangible sign of a student learning from its masters.

The House of Wisdom: A Library Built from the World's BooksThe intellectual heart of this project was the Bayt al-Hikma, or the House of Wisdom, in Baghdad. It was not merely a library but a massive translation bureau, research center, and university rolled into one. Under caliphs like Al-Ma'mun, it became the engine of the Golden Age.

Its mission was breathtakingly ambitious: to gather all the world's knowledge and translate it into Arabic. Scholars—Muslim, Christian, Jewish—were hired to translate works from Greek, Persian, Syriac, and Sanskrit. This was not a passive act of storage, but an active one of rescue and integration.

- They saved the works of Aristotle, Plato, and Galen from the obscurity into which they had fallen in Europe.

- They merged Greek logic with Persian statecraft and Indian mathematics.

- They studied the medical texts of the ancient world and built upon them.

This was the true "conquest": the systematic gathering of the intellectual heritage of humanity under one roof, creating a common scientific language—Arabic—that allowed for unprecedented collaboration and advancement.

The Student Becomes the Master: From Translation to TransformationThe Arabs did not stop at translation. They became the world's greatest innovators, taking the knowledge they had learned and pushing it into realms the original authors could never have imagined.

- Al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850): A Persian scholar in Baghdad, he didn't just learn Indian mathematics; he revolutionized it. In his book Al-Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala ("The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing"), he gave the world:

- Algebra (from al-Jabr).

- Algorithms (a Latinization of his name, Al-Khwarizmi).

- The decimal number system and the concept of zero (adapted from India, but introduced to the West through his work).

- Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037): His monumental The Canon of Medicine was a medical encyclopedia used in Europe for centuries. He shifted the focus from cure to prevention, systematized the understanding that diseases have specific transmission vectors, and made groundbreaking contributions to philosophy and physics.

- Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1040): In his Book of Optics, he dismantled ancient Greek theories of vision. Through rigorous experimentation, he proved that light travels in straight lines and enters the eye, establishing the foundations of the modern scientific method centuries before the European Renaissance. He also made early conjectures about the nature of gravity and inertia.

The Islamic Golden Age was not an alien culture imposing itself on the world. It was the culmination of the existing "Western" tradition—the Greek, Persian, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian knowledge—preserved and radically advanced at a time when much of Europe was intellectually fragmented.

The Arabs were not destroyers; they were synthesizers, patrons, and innovators. Their conquest was unique because its greatest victory was not over armies, but over ignorance. They built a civilization where a question was valued more than a dogma, and where the pursuit of knowledge was considered the highest form of worship. When this knowledge finally filtered back into Europe through centers like Muslim Spain and Sicily, it didn't introduce something foreign—it reintroduced the West to its own forgotten legacy, sparking the Renaissance and setting the stage for the modern world.

Comments (Add)

Showing comments related to this blog.